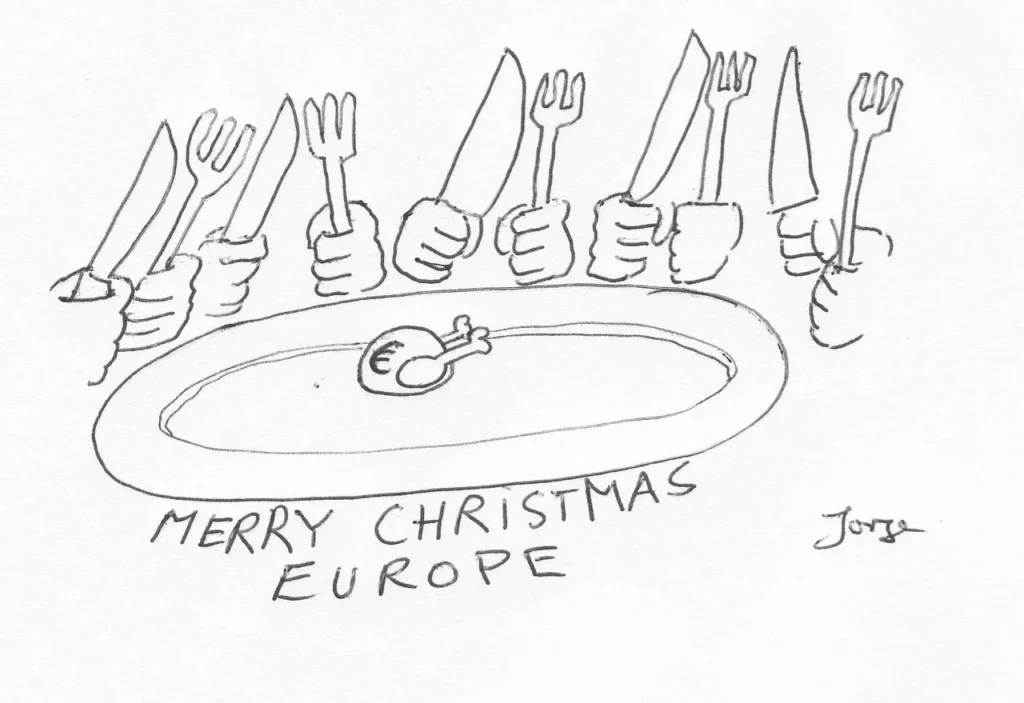

New EU Own Resources as a Christmas present

23 December 2021 – Jorge Núñez Ferrer

While it may be a present for some, for a researcher like me it certainly is frustrating to discover a major legislative proposal the day my vacation was meant to start. Nevertheless, the subject deserves a first personal assessment, which may be followed with a more formal analysis – after vacations.

The European Commission has proposed to introduce new resources between now and 2026:

a) A share of the revenues of an extended Emissions Trading System (ETS)

b) The revenues of a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM)

c) A tax on a share of profits from the worlds’ largest multinational enterprises relocated in EU Member States

The Commission has released a user friendly yet minimalistic factsheet presenting the three proposed resources. For those wanting to challenge their brain in a more technical and complex language, a communication and two legislative proposals await them here. This little commentary gives a first assessment between and behind the lines, food for thought, as the practical challenges are not addressed by the information provided.

The three revenues have common characteristics, they are raising revenues that are additional to existing national taxes and targeting sources which member states cannot tax effectively individually. This has the objective to reduce resistance to the new sources of revenue. The three are also targeting politically acceptable areas, considered also as having some popular support, namely emissions, foreign companies and …. large foreign companies.

The three revenues will not be enough to raise the funding necessary to cover the full annual costs of reimbursing the borrowed funds for the EU recovery programme. The Commission will thus propose further resources by the end of 2023 to enter into force in time for the next Multiannual Financial Framework post 2027, when the repayments will start to be significant.

Popular support or not, putting the instruments into practice will not be easy. Let’s try to give an assessment in a nutshell for each of the three:

1. A share of the revenues of an extended Emissions Trading System (ETS)

Of the three, this is the easiest to set up, because the ETS already exists. It first proposes to allocate 25% of the existing ETS to the EU budget from 2023 and it extends the ETS coverage to maritime transport and aviation, which was anticipated for a long time and is technically relatively straightforward. Then it follows with a more controversial extension of the ETS to transport and buildings from 2026. The revenues of all these extensions of the ETS coverage will accrue to the EU in full.

Overall, the revenues should raise on average €9 billion per year. For the latter, the Commission proposes to counterbalance the negative effects with a Social Climate Fund, which was already proposed in July 2021. This fund should use a share of the revenues to compensate those most affected, avoiding European-wide ‘gilets jaunes’ protests of angry citizens ravaging city centres.

Strengths:

The proposal to use 25% of the ETS revenues is relatively uncontroversial, as it does not affect the funds member states retain for modernising their energy sector, and because contributions are corrected for poorer member states with high emissions.

The extension to the maritime and aviation sectors is relatively uncontroversial, although some complications may arise with issues relating to taxation or exempting flights or ships entering or exiting the EU borders. Transport and buildings are a very important source of emissions, and this extension can provide part of the market incentives needed to push for an accelerated shift to low emissions transport modes and energy efficiency investments in buildings.

Weaknesses:

It is difficult to get the compensation right of an extension to transport and buildings for cost impacts on households and small businesses. In this area the possibility of popular rejection is high.

Increasing the EU budget with the Social Climate Fund is likely going to be rejected by net contributing member states. As a counter argument, initial impacts could be covered first by the recovery funds and later by funds not used over the Multiannual Financial Framework using flexibility instruments.

2. The revenues of a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM)

This has been a darling of many politicians and strongly coveted by some governments interested in protecting industry from foreign competitors. In order to avoid the controversial use of tariffs, the system is based on selling carbon border adjustment mechanism certificates to EU importers. This will increase the cost of imported goods to reflect the cost of domestic products under the ETS, and 75% of the revenues will accrue to the EU.

Strengths

It represents a solution to reduce potential carbon leakage avoiding a clear controversial tariff and reduces resistance to further extending the ETS. The model could be applied to other sectors which in the future might be subjected to carbon taxes.

Weaknesses

A border carbon adjustment cost to importers in any form may face difficult challenges with trading partners at the WTO. Despite its design as an internal charge for certification, it still could be challenged as a non-tariff barrier to imports, which can be challenged. This will depend on the implementation system.

It may become rather complex to implement, while only raising an estimated €0,5 billion in annual revenues from 2023 to 2030, which may not be attractive enough given the potential conflicts with large trading partners.

3. Taxing residual profits of the largest and most profitable multinational enterprises

This is based on an agreed principle by the OECD/G20 members to introduce a mechanism to counter tax avoidance by large multinationals that relocate profits to low taxation jurisdictions. Some of the profits would be retained in the end market jurisdictions, i.e. where the goods and services are consumed or used. The OECD agreement lacks details and so does the Commission proposal, which announces that it will design and propose a Directive to define the modalities to collect this tax. The annual revenues for the EU budget are estimated by the Commission to amount to €2,5 to €4 billion.

Strengths

This proposal addresses the concerns that some multinational companies avoid taxation on profits generated by sales in the countries they operate in. It reduces the tax erosion emerging from a global economy, especially for digital services. With the agreement at the level of the OECD/G20 there is a real possibility for such a system to be accepted without conflicts with major trading partners (e.g. the USA).

Weaknesses

The agreement in the OECD/G20 does not provide implementation details, there is a possibility that the EU may end designing a system before there is an international agreement on the modalities. While the European Commission’s work may help influence the direction of the OECD/G20 discussions, it may also be received negatively if it proposes a Directive earlier to an international agreement. It is a very delicate subject particularly for the US.

The road will not be easy

Of the three solutions, only the allocation of 25% of the present ETS revenues (and maybe the extension to maritime and air transport) is straightforward and easy to implement. The other proposals, while apparently simple in the way they are presented, face very serious challenges. How the European Commission handles the preparation of the Directive and the relations with major trading partners and the OECD/G20 group will be essential for the proposals to become a reality.

To conclude, if this were a film, I would propose to tax popcorn as an own resource, as the negotiations will be tense and interesting to follow.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

COPYRIGHT © 2021 CEPS – EU RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE MONITOR – ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.